Written by Peter Pearsall and Rick Vetter/Photo by Rick Vetter

Christmastime is all about traditions. Getting together with friends and family, exchanging gifts and good wishes, reflecting on one year’s end and looking forward to the next—all are part of the yuletide tradition, celebrated annually around the world.

Depending on which circles one moves in, Christmastime is also about birds —live birds, in situ. Not just basted turkeys. Nor that mixed flock of “four calling birds, three French hens, two turtle doves and a partridge in a pear tree”. The Audubon Society’s Christmas Bird Count, a citizen science effort aimed at monitoring bird population trends on a massive scale, is a long-standing tradition dating back to 1901. Born from an entirely different aim—that of shotguns trained on as many birds as one had shells for—the now-bloodless count turns an age-old maxim on its head: birds in the bush are worth infinitely more alive than dead by one’s hand, any ratios notwithstanding.

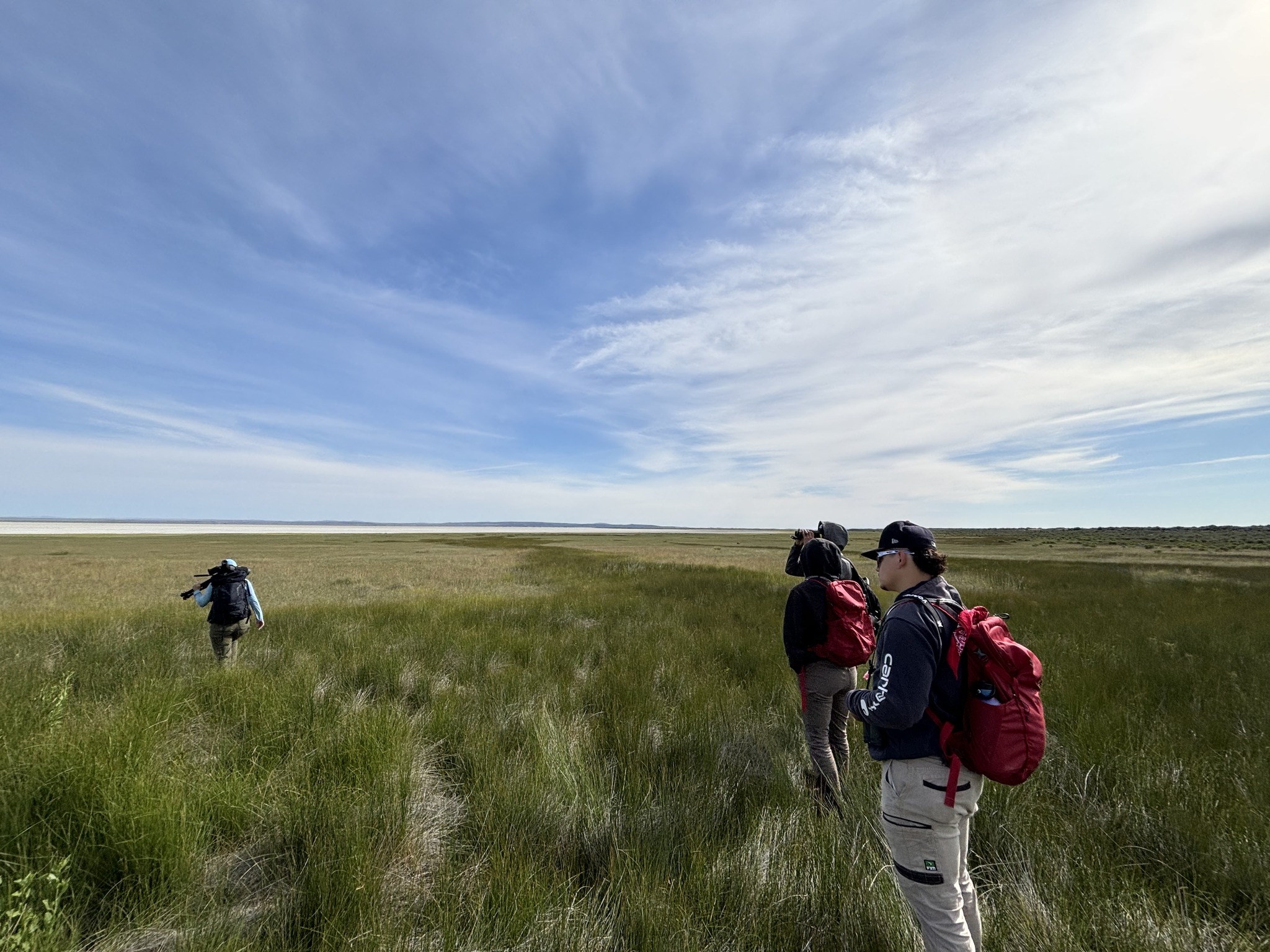

Now in its 124th year, the count draws more than 70,000 volunteer birders from across the Americas. They spend a day (or several days, contingent on their ardor) counting wild birds within a prescribed circle 15 miles across, sunrise to sunset. (Often a few hours are added after dark, to include nocturnal species). They move in flocks, much like their quarry, toting binoculars and spotting scopes and clicky metal tallywhackers for counting large, clustered groups of birds. They bicker and henpeck among themselves, among rival birders, because it is their contentious nature to question the observations of others, to remain unsatisfied until the putative bird is glimpsed with their own eyes.

As far as Christmas traditions go, counting birds makes about as much sense as the rest. That is, it does not, strictly speaking, make sense. It is an arbitrary artifact. Partly out of tradition (the shotgunning of yore was a holiday affair) and partly out of convenience (Christmastime affords people time off from work to do other things, such as watch birds), the count occurs from December 14 to January 5. This practice of citizen science is an inexact one, as amateurs and hobbyists are allowed—nay, encouraged—to participate in the count. Mistakes are unavoidable. But with enough counters involved, and with enough counts done successively in discrete areas, a fuzzy-edged census emerges, one that can be compared with those of years past and inform future conservation efforts.

The CBC in Burns, Oregon, has taken place since 1998. The one at Malheur Refuge’s P Ranch is more venerable, dating back to 1945.

The Burns count is famous for its California quail tallies. These small game birds, incredibly numerous in Harney County, play a notable role in the Burns/Hines CBC. Backyard feeders concentrate quail flocks in winter, and in 2004 CBC participants counted a staggering 10,011 quail in Burns and Hines, setting a world record for the highest number of California quail found during a CBC! This broke the previous record of 6,800 set in Orange County, California in 1963. Shortly afterward that record-setting 2004 count in Burns, populations of quail and chukar crashed across southeast Oregon, resulting in a low count of 2,123 quail in 2007. Their slow recovery might be attributed to an increase of feral cats in Burns and Hines. The ceremonial town Christmas Tree is also a factor, since the city cuts one of the largest spruce or similar trees in town for free each year. These trees are the favorite roost of quail to avoid great horned owls at night.