By Matt Stuber, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service; Raptor Biologist, Division of Migratory Birds

Across many western states, biologists are embarking on a challenging adventure. That adventure? To learn more about short-eared owls. I am proud to have brought a part of that adventure to one of the great Oregon public spaces – Malheur National Wildlife Refuge (NWR).

Short-eared owls are an open-country species that has been shown to associate with diverse habitats, including tundra, marshlands, grasslands, shrublands, and even agricultural lands. They seem to be flexible in the type of habitats they select in any given year, and probably select habitat based on prey availability.

However, despite an apparent adjustability to different habitat types, there is some reason to be concerned about the stability of short-eared owl populations. First, they are listed as endangered in 12 U.S. states (not including Oregon), and are named by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service as a Bird of Conservation Concern in 18 of 34 terrestrial Bird Conservation Regions. Additionally, a 2014 study by Alaska Fish and Game biologist Travis Booms pointed out evidence of a long-term, range-wide decline of short-eared owls in North America, based on Breeding Bird Survey and Christmas Bird Count data.

Conversely, recent data collected over several years and in eight western states by citizen scientists (known as Project WAfLS) suggests that short-eared owl populations might be stable, at least in recent years. However, consistent with the species’ known flexibility, owl populations seem to be shifting in local abundance from state to state. Project WAfLS biologist Rob Miller believes it is likely that these movements are caused by local prey cycles. In other words, the owls go where the prey are abundant.

While this plasticity is probably beneficial to the owls, it makes life a bit difficult for the biologists trying to study them. Trying to study a population of birds that may prefer parts of Wyoming one year and parts of southwest Idaho and eastern Oregon the next year poses some challenges. Truth be told, we are not able to predict where these owls will be most abundant in any year, and we know relatively little about some basic aspects of short-eared owl ecology.

However, across the West, efforts are underway to change that. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, as well as many western state governments, have recently dedicated resources to answering some important questions about this understudied species. In the spring of 2020 Miller, a biologist from Boise State’s Intermountain Bird Observatory, formed a team of biologists across the west. I am proud to represent Oregon on that team. The team’s goal is to learn more about poorly understood aspects of short-eared owl ecology, including breeding phenology, home range size, dispersal, migration, and sources of mortality (to name a few). My job on the team is to find and capture a short-eared owl in Oregon and deploy a GPS/GSM transmitter on that bird. Data from that transmitter will help us answer some of these important questions.

These owls will be in good hands—literally. I am permitted by both the federal Bird Banding Laboratory and the State of Oregon to conduct this work. On top of those permits, I have many years of experience studying and safely capturing and handling all types of raptors.

I chose Malheur NWR as a place to begin my summer field efforts in 2021. Short-eared owls regularly call Malheur NWR home during the breeding season. Because of the owl’s nomadism, there are only a couple other places state-wide that produce fairly regular short-eared owl sightings in the summer. This year was no exception at Malheur NWR. In fact, Refuge staff and volunteers (thanks Alexa Martinez and Rick Vetter!) were reporting relatively high short-eared owl numbers this summer. As a result, it didn’t take any arm twisting to get me to the refuge. Successful capture or not, spending time at Malheur NWR in May (or any month, really) is always time well spent.

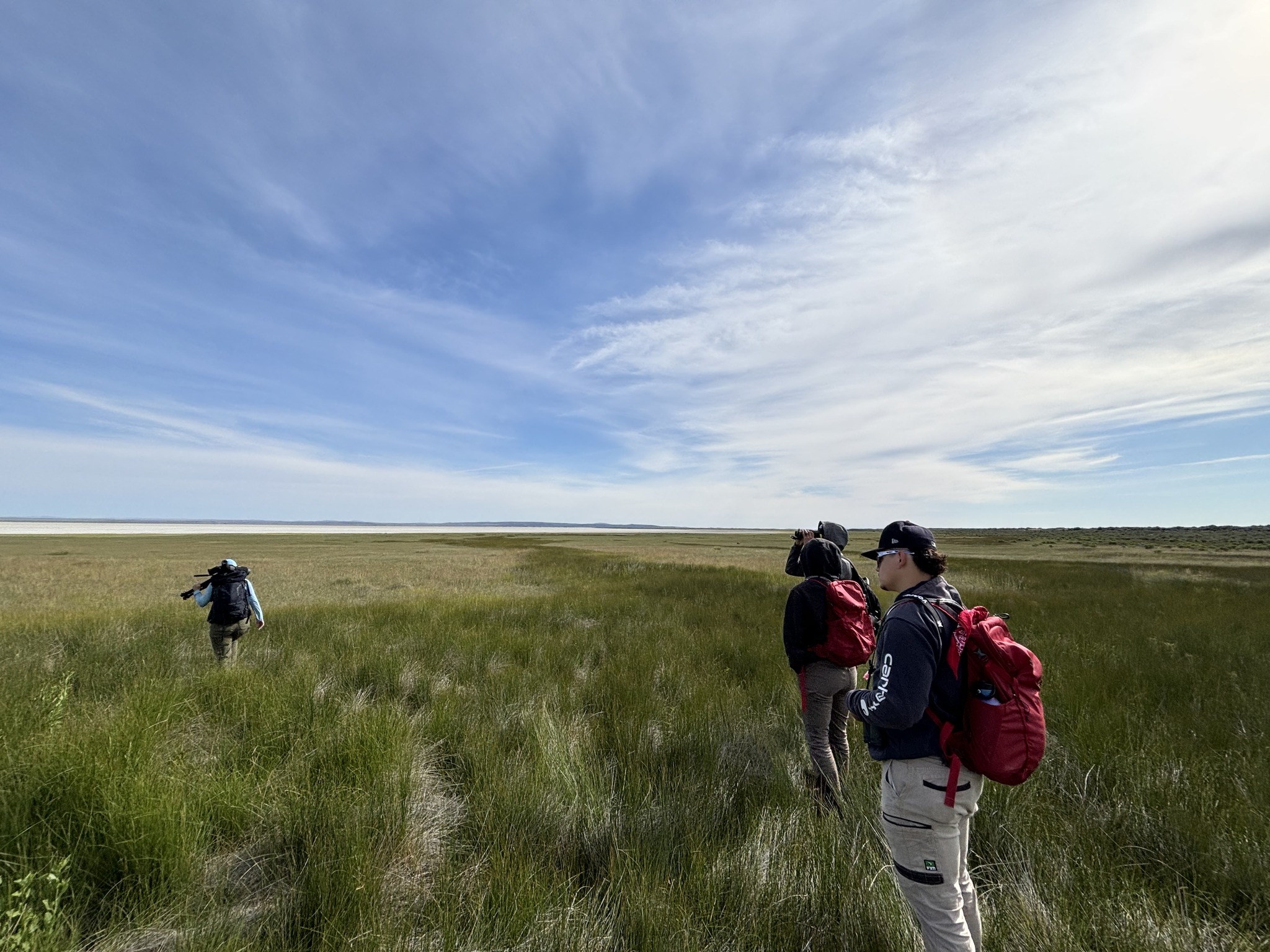

When I arrived at the refuge on May 30th, the dedicated staff helped me get right to work. We started scouting areas where short-eared owls had been previously observed. In all of the areas Refuge staff took me, we observed breeding behavior and suspected nesting was underway. Refuge staff and I speculate that we know of four breeding territories on the Refuge. I’m sure there are others as well. However, despite hours of observation for three straight days, and some searching of an area where we commonly observed owls, we were unable to locate a nest.

Trapping raptors during the breeding season without the knowledge of an occupied nest location is typically difficult. Nests give biologists two advantages when attempting to trap a bird. First, it is a place we know that the adults will visit. So there is a good chance that, with patience, a bird will come to a trap if placed near a nest. Conversely, a trap randomly placed in a field with no knowledge of nest location has a low likelihood of being seen by a target bird. Second, raptors (and other birds too) typically defend their territories, nests, eggs, and young. Biologists can sometimes try to use the bird’s natural nest defense behavior to their advantage when attempting to capture it.

After many days of observation and several attempts at trapping the “harder way” (i.e. traps set with no knowledge of nest location), I decided to give the owls a few weeks and return when discovery of a nest is more likely. On June 1 I departed, hoping to return again in late June for another attempt at nest discovery and trapping success.

Amazingly, on my way home I stopped at the Summer Lake Wildlife Area (managed by Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife). That night, with the help of Area staff, I was able to locate a short-eared owl nest and capture a healthy adult male. Unfortunately, he only weighed 10.5 ounces and was too small for a transmitter. Consistent with his best interest, we banded and released him with no transmitter deployment. Hopefully, birds we trap in the future will be a little bit larger and more capable of safely carrying a transmitter for our study. I am optimistic that a return trip to Malheur will result in a successful capture and transmitter deployment, and several years worth of data that will help us learn and better manage short-eared owl populations in the West.

NOTE: Successful capture efforts took place at Malheur NWR this last weekend (June 25th-27th). Be sure to check out the August edition of our newsletter for an update from Matt Stuber and Alexa Mertinez.