Written by Travis Miller, Malheur NWR Supervisory Ecologist

Feature Image: Chinle Wash, Russian olive grayish green and native cottonwood larger bright green trees. Photo by Linda V. Reynolds.

Russian olive (Elaeagnus angustifolia) is native to Europe and western Asia and was introduced to North America in the early 1900s. It was widely distributed across the United States for purposes such as windbreaks, wildlife habitat, ornamentals, shelterbelts, and soil stabilizer along eroded water ways. This use and its ability to thrive under a wide range of ecological conditions led to a rapid expansion and became invasive (feature image above, in the Southwest).

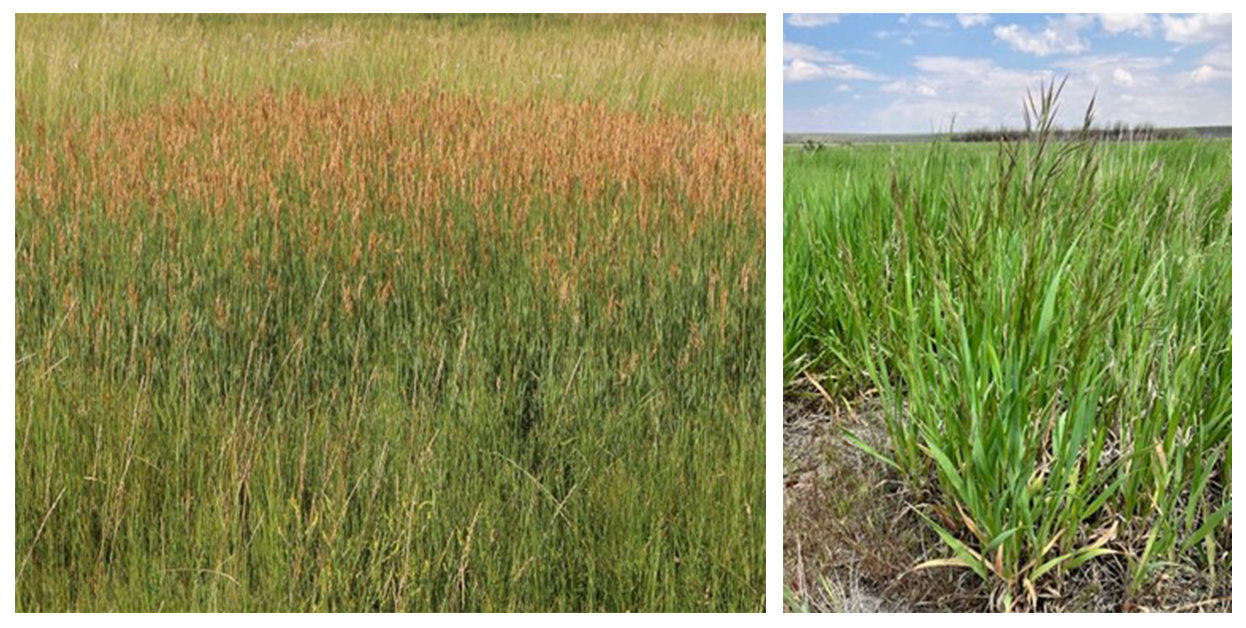

In some states such as Montana it is listed as a Priority 3 species where intentional spread and sale are prohibited. Russian olive prefers a water table near the soil surface like riparian, riverine, lake/marsh shorelines, wet meadows, springs, woody riparian, saline lake shorelines, and irrigation ditches, which makes Malheur National Wildlife Refuge the perfect environment for this exotic species to establish and spread rapidly. As with many invasive species the early phase of Russian olive invasion can bring beneficial diversity to habitats by adding more structure and food, but within a short spatial and temporal scale of one to two decades exponential growth in population occurs.

The last refuge effort to remove this species occurred in 2011 and by 2024 the invaded footprint has been reclaimed and, in some areas, increased such as Briggs Bay, the Narrows, southeastern shoreline of Malheur Lake, and Frenchglen. It is not feasible to eradicate this species at Malheur Refuge because it is well established in the Harney Basin and fruits being highly sought after by birds for its fleshy high energy seed coating are eaten and distributed through scatt across the landscape.

Currently the best management approach is to keep Russian olive trees at a low and manageable number by cutting the trees before reproductive maturity and spraying the stump or otherwise they will resprout. In the last two years the refuge has been implementing these treatments working to remove trees from the aformentioned areas. This work is difficult and costly because in areas such as Briggs Bay (photo 2) the tree density is high and if you have never approached one before they are full of long ridged spines that can puncture clothing, gloves, shoes, and tires. Current treatment efforts have been funded through the Refuge’s Hay and Rake-bunch Graze Program utilizing the Harney County Weed Program’s SWAT (photo 3). For more information on Russian olive physiology and management there are three references listed below.

USGS. 2010. Saltcedar (Tamarix spp.) and Russian Olive (Elaeagnus angustifolia) in the Western United States – A Report on the State of the Science. Fact Sheet 2009-3110.

USDA. 2019. Russian Olive. MT-2019. May 2019.

USDA. 2014. Field Guide for Managing Russian Olive in the Southwest. TP-R3-16-24.